„We cannot live our lives and tell their story.”

(Fawzia Zouari, My Mother’s Body)

“Anything can be recounted, my daughter: the kitchen, the war, politics, fortunes, but not what goes on in the privacy of a family. This would make it visible twice. Allah has taught us to shroud all secrets and the first of all secrets is the woman!” These are the words of Yamna, the protagonist whose life is recomposed by the recollections of those who knew her, to her daughter, who left her native Tunis and settled in France. Yamna is the mother, but equally so the matriarch, the undisputed mistress and keeper of all the secrets of her kin. And this is precisely the narrative pretext in Fawzia Zouari’s novel „Le corps de ma mere” („My Mother’s Body”).

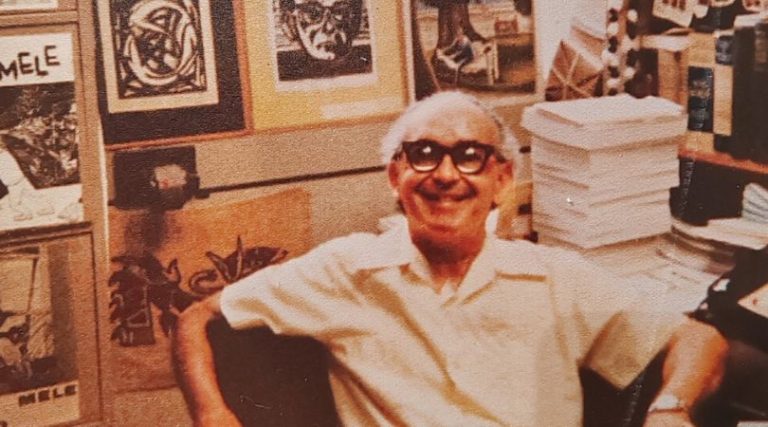

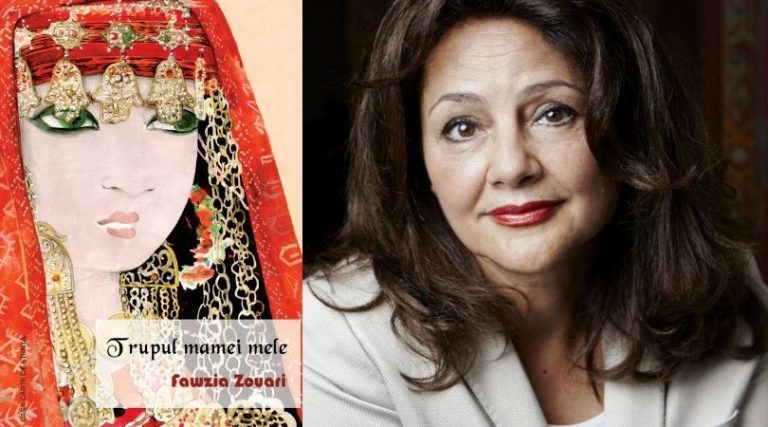

A writer and journalist of Tunisian origin, with a Ph.D. in French and Compared Literature, Fawzia Zouari has published several novels, among which „La caravanne des chimères” (1989), „Ce pays dont je meurs” („I Die by This Country”, 1999) or „La deuxième epouse” (2006), but also the exquisite volumes of essays „Pour en finir avec Shahrazad” (1996), „Le voile islamique” (2002), „Molière et Shéhérezade” (2018). Published in 2016, „Le corps de ma mere” („My Mother’s Body”) was awarded the Comar d’Or Prize and the Prix des Cinq Continents de la Francophonie (Francophonie World Prize). Highly acclaimed by critics and readers alike, „My Mother’s Body” is not just the touching story of a woman’s life in Tunis prior to the Jasmine Revolution, but also the sui-generis history of an entire civilization and of the traditional world of the Bedouins. It is a story equally meant to reconnect the long departed daughter – living in France and convinced that she is fully integrated into the Western world, into its culture and language – with the values and rules of a world with which, even if she physically left, she is still connected, though at times she is rather reluctant to admit it. Here is what Fawzia Zouari herself wrote in this respect in her volume of essays entitled „Molière et Shéhérezade”, implicitly defining the experience of the physical and spiritual exile as well as that of the two languages and cultures that have shaped her entire life and her cultural background: “I do not withstand, as if letting myself swim with the tide. I tell myself that there is a single language, a universe of its own. A realm of words, of stories and figments. All you have to do is make room for yourself in there, bring along your innate metaphors, your stories and dreams and start grafting your ancestors’ effigy on the tree branches of other forefathers, plant your memories on land already ploughed, stay silent in order to let out your inner voices, build other mausoleums and collect yourself at other graves. And here I am in-between two planets/ languages. And neither is there any drama nor does one feel in exile. For it is up to me to be a bridge between them.”

„My Mother’s Body” is divided into three parts (‘My Mother’s Body’, ‘My Mother’s Story’, ‘My Mother’s Exile’), a ‘Prologue’ and an ‘Epilogue’. The text, strewn here and there with touches of „The Arabian Nights” but also imbued with unexpected fragments narrated in an ironic or comical mode and with entire pages of profound reflection whereby the author unhesitatingly posits certain truths about the Arab world (girls’ illiteracy and their limited access to education, domestic violence), tells the life story of Yamna, the protagonist’s mother. But the novel is also an extraordinary journey into the history of Tunisian culture, a courageous and insightful exploration of a quintessentially patriarchal world, nevertheless one in which the power and the influence of women are indisputable. So that Yamna’s life, and equally so the lives of the women in the Bedouin tribe which she is part of, is an epos of suffering and renunciation, of hidden tears and accepted failures but, in certain moments, the same life becomes a celebration of beauty, of self-confidence, of the drive to move forward irrespective of the problems encountered. “Yamna’s reputation for elegance had gone beyond borders. The ladies asked to be brought ‘Yamna kaftans’ or ‘Yamna fuchsia’ cloth. They admired Fares’s wife, who would wear two overlapping pieces of material […] so that one could look at her for hours as if looking at a music box exhibited in the window of a jewellery store, the refrain of which would be her beloved sentence: ‘Tell the Sun to shine or I’ll shine instead!’”

The story begins in the spring of 2007, when, in a hospital in Tunis, in her last days of life, Yamna is surrounded by her children, Noura, Jamila and Souad, who are joined by her daughter – their sister, respectively – who has been estranged for years, since she left home and settled in France. And it is here that the one initially regarded as a stranger, no longer able to understand her family and her people, is trying as hard as she can to find out everything about her mother, to discover all the secrets which, in her adolescence, Yamna refused to disclose or share with her, convinced that a woman’s power also consisted in her aptitude to carry her own secrets to the grave. Equally impressed and troubled by the feebleness of her mother, whose hair and disrobed body she has never seen before, the French woman recalls her past, trying to understand now, years later, why certain things happened and, moreover, why they happened as they did. Permanently sensing that she is missing something, that something undefined or impossible to understand always lingers behind, she has the chance to talk, at last, to Naima, the woman who has looked after and accompanied her mother in recent years and who is her real inheritor, as Yamna has more than once told her. And Naima will reluctantly tell her the story of her mother. And only now the veils drawn over things seem to be lifted and the secrets that have been so well-kept are disclosed; or at least part of them. Now it turns out that Yamna’s father, Gadour, the one called the ‘Lion of the Valleys’ because of his numerous extra-marital affairs, had deeply hurt her mother, Tunes, by taking a younger second wife. Ignored, when in labour, by the only midwife in the area, who chose to help Gadour’s second – but younger – wife and eventually departed from the living because of the ensuing child-birth complications, Tunes asked Yamna, a little girl at the time, to never ever allow her future husband to take a second wife. In keeping with that promise, Yamna would always hold a grudge against the other woman, whom she considered responsible for her mother’s premature death, but she would impose her will on her husband, Fares, whom she would often defy and even threaten to kill, should he ever dare bring another woman into their home. Years afterwards, when Fares is no longer among the living and the children have gone their own way, Yamna ‘s behaviour has become incomprehensible to those around her. For, having adamantly consented to leave her home, that traditional world which she knew and where she could find her way about and impose her will, she has ended up living in Tunis, looked after by her daughters and son, but misunderstood by all of them. Full of anger at times, inclined to despise the others and often using a scurrilous language, she seems to be another – different – Yamna after relinquishing her native land. Only Naima understands her and, years later, so will her daughter, who arrives from France to this forlorn place that she can barely call ‘home’ anymore. Yamna is no longer herself for, since her enforced departure from the land of the Bedouins, she has no longer known how to live, but, on the other hand, paradoxically – but only apparently so – she wants to live. She wants to live and feel that she is a woman – admired, gazed at, loved – because, in her long years of reign and domination over her entire family, she felt she was nothing more than wife to Fares and mother to her children, almost never a woman…

The novel captivates by the author’s ability to say even those things that the men and especially the women of the Arab world are shy of saying, by its expressiveness, by the dauntless exploration of areas that most often remain shrouded by the veils that cover the lives of women in Tunis – and not only. And, as Boualem Sansal wrote in his review of this novel, “Fawzia Zouari gives us an extraordinary family story, Shakespearean in terms of framework, expanse and style, a story in which readers are warned that they will be caught in a whirl from the very first pages, that they will find it impossible to evade the desire, full of peril, to glance inwards and to ask questions about the history of their own families. They will read Fawzia Zouari’s story and at the same time they will delve deep down into their souls.”

Fawzia Zouari, „Le corps de ma mere”/ „Trupul mamei mele”, translation into Romanian by Alexandra Ionel, Casa Cărții de Ştiință Publishing House, Cluj-Napoca, 2020

Translated into English by Mirela Petrașcu

Scrie un comentariu