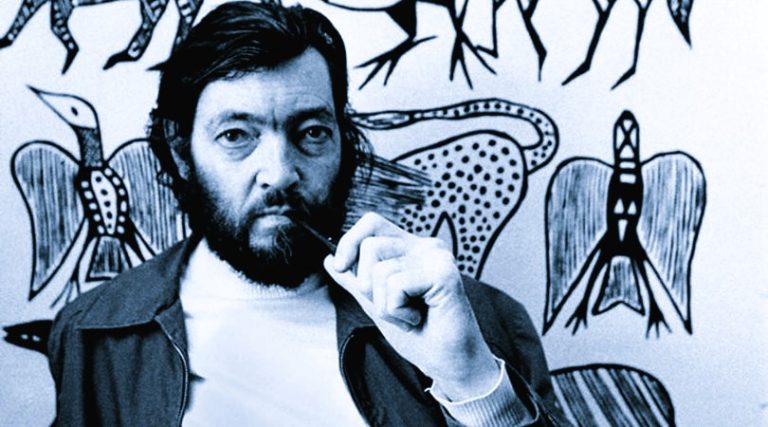

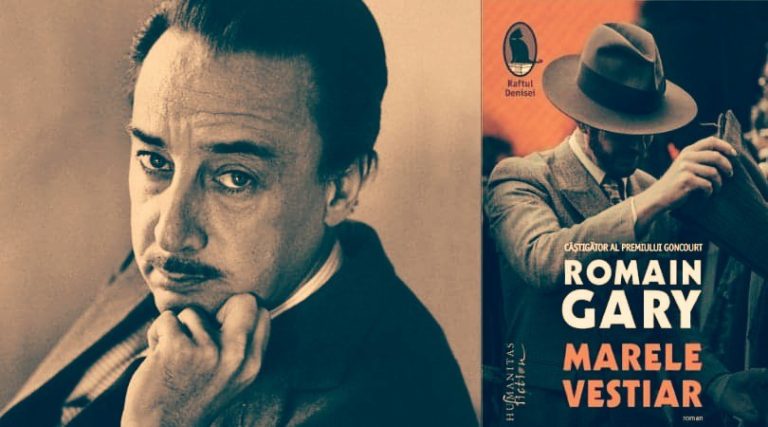

He was born in 1914, into a Jewish family in Vilnius, and grew up in Warsaw, where he received Catholic baptism. He subsequently settled in France, where he read Law and cultivated his amazing linguistic skills, being fluent in six languages. During World War II he was an aircraft pilot in the Free French Air Forces, a stalwart of the French Resistance and he was decorated for his deeds of arms, receiving the very title of Commander of the Legion of Honour. After the Peace Agreement he became a diplomat, with a prodigious activity both in Europe and in the United States of America. He was the only writer to have received the Goncourt Prize twice and his name is, obviously, Romain Gary (with the second Prix Goncourt awarded to Émile Ajar – Gary himself -, as Ajar’s true identity was disclosed only after the writer’s death). His work, spanning over more than four decades, is vast, complex and heterogeneous, comprising over thirty volumes of novels, essays and short stories, of which some compelled amazing recognition in France (such as „La vie devant soi”, the top-selling French novel of the twentieth century), while others were prematurely clouded up by the numerous controversies that sparked right after the death of writer (who shot himself in 1980), especially with regard to the fictive identity under which he had published some of his texts.

Aside from all the debates and disputes, Romain Gary has remained one of the iconic voices of twentieth-century French literature, a writer whose work has never ceased to capture interest and who brought to the foreground even topics often regarded as taboo in the Hexagon. Such is, for instance, the case of „Le grand vestiaire” („The Company of Men”), his novel published in 1948, which has recently been translated into Romanian and published by Humanitas Fiction Publishing House (“Raftul Denisei” Collection), in an outstanding version signed by Adina Diniţoiu (who is, on a related note, well acquainted with the French and Francophone cultural space, having translated, in an equally inspired manner over the course of recent years, emblematic writings by authors such as Françoise Sagan, Belinda Cannone, François-Henri Désérable, Raymond Aron or Antoine Compagnon).

The pretext that „Le grand vestiaire” draws on is, at least at first sight, a rather simple one, especially in the context of the aftermath of World War II. Thus, Luc Martin, the protagonist and narrator, is one of the ever so many children orphaned by the War. Aged fourteen, he falls under the so-called protection of Vanderputte, a devious charlatan skilled at appearing to be in the know about everything, who runs an actual gang of teenagers whom he is determined to initiate into the secrets of … larceny: which actually happens and, alongside other teenagers, Luc starts filling Vanderputte’s apartment, le grand vestiaire, with stolen goods. But things take a more complicated turn and Luc will find himself in ever more difficult situations, for Vanderputte proves to be a collaborationist; moreover, one of those who, during the War, had denounced Jews. Imperceptibly, for Luc the universe seems to shift into a great, fully-stocked storehouse, yet one in which one can no longer find genuine human warmth or figure out the truly right path or the right road to take. To further complicate things, the protagonist falls in love with Josette, who is the sister of Léonce, one of his companions and an orphan himself, with whom he devises several business deals on the Paris black market, meant to enrich them and to make them resemble the lead characters in the gangster American movies that they adore watching. However, tough reality will beat any form of fiction, compelling as it may be. Similarly, the challenges that Luc will face along the way will be ever tougher.

Upon its publication, „Le grand vestiaire” received rather cautious response in France, both from the reading audience and from literary critics, given the writer’s courage, at that time, to bring up many (and crucial) truths that had defined the turbulent years preceding and succeeding the end of the World War and to address a series of issues that were conspicuously swept under the rug for quite a long while in France: most definitely, the issue of antisemitism, manifest in the Hexagon especially before and during the first half of the War. Consequently, the novel failed to sell from 1948 to 1949 and it received favourable response only after it was published in the United States of America in 1950, under the title „The Company of Men” (translated by Romain Gary’s wartime good friend Joseph Barnes, who then served as coordinator of the European Edition of the prestigious ‘New York Herald Tribune’). And if, in the late-1940s France many readers found „Le grand vestiaire” a much too ruthless mirror suddenly placed in front of a society not yet prepared for such a challenge (and confrontation!) intended to disclose the truths, be they painful, of an age just prior to the present of the plot, as well as of the deeds and choices of some people who had unhesitatingly betrayed fellow-beings who had found themselves in a hopeless situation, across the Atlantic Gary’s novel was read from a different perspective and the text suddenly dissipated the author’s aura of enthusiastic idealist, instantly becoming, for the general public (as the keen ‘New York Times’ literary reviewer readily emphasized), the French replica of „Oliver Twist” (a detail that went completely unnoticed in France!), while the American exegetes also highlighted Gary’s deftness at delineating the grim destiny of an entire “lost generation” in post-War Paris.

But certainly, this novel by Romain Gary stands proof not only to the writer’s ability to reclaim, by means of re-contextualization, an important character of Victorian fiction, but also to the manner in which the author related to the culture of previous ages. Because a close reading focussed on the significant details will reveal that the small gang of thieves in post-Liberation Paris is nothing but the French embodiment of the famous characters Rinconete and Cortadillo and of their apprenticeship in larceny under the guidance of Manipodio, in Miguel de Cervantes’s volume of ‘novellas’, „Exemplary Tales”. A novel expression of the evolution of such picaresque characters, the existence of Luc, Léonce and Josette also proves, therefore, the aesthetic viability of the picaresque prose formula, for the greater or lesser adventures and enterprises of the teenagers fascinated by the American cinema and by the illusory glamour of the Hollywood world, dreaming of wealth and of resounding business undertakings, also represent the link – however unexpected, but nevertheless extraordinary – that Gary established, over time, with the great literary models of the Renaissance. Equally a novel of the human condition and a meditation on human loneliness and on the contentious issues of a period that was tumultuous and turbulent from many points of view, „Le grand vestiaire” has remained to the day an excellent attempt at assessing the highly complex relations between the guilt of the past regarding, on the one hand, the attitude towards the Jewish community that some of the French people had started adopting (even without having the courage to openly admit it) and the utopian hopes about a triumphant, perfectly structured socialism meant to save society from all the shortcomings of capitalism, on the other hand…

Certainly, Gustave Vanderputte is, in the context of Gary’s book, Charles Dickens’s new Fagin, a modern (and French) Fagin. But the similarities with „Oliver Twist”, which hove into view at the level of both plot-devising and character-shaping, do not end here. Nancy, the “free and agreeable in manners” yet gold-hearted woman, is replaced with Josette, with whom Luc has a passionate love affair. Unlike Nancy, Josette dies of tuberculosis, and by this plot twist Gary hinted, in an unexpected flip of aesthetic register, at Alexandre Dumas’s „The Lady of the Camellias”. Literary critics further identified characters devised more or less as mirror images of Dickens’s ones: René Kuhl, for instance, is the counterpart of Sykes, while Sacha Darlington is the filigree image of Toby Crackit. However, one should take into consideration yet another important element: even if he creatively recurred to and originally re-interpreted a series of characters, images or instances present in „Oliver Twist”, Romain Gary did not do it in order to replay the albeit remarkable models of earlier literary works, but in order to offer his readers potential answers to the questions that the present, and equally so the past, might pose. Hence the shifts of perspective and their depictions in a different key, as if Gary were looking at Dickens’s canonical characters through a warped looking-glass. Let us consider, in this respect, a single example: Fagin was a Jew, but Dickens was not; while Gary was of Jewish descent, Vanderputte, the new-fashioned Fagin, was anti-Semitic. With Dickens, Fagin was a sort of elaborate caricature of the Jew, consonant with the manner in which he was oftentimes portrayed in the Western fiction works of the time, but after Auschwitz the perspective changed dramatically – hence the different features of the charlatan in „Le grand vestiaire”. Gary was one of the first French writers who attempted, in the late 1940s, to bring up these delicate issues (alongside Marcel Aymé in his „Uranus”/ „The Barkeep of Blémont”, where the “Jewish question” was nevertheless carefully avoided, although the writer forthrightly castigated the hypocrisy of the French politicians after the Liberation) and to discuss the relations between the Jewish community (or its representatives) and the majority population in France.

On the other hand, Romain Gary also managed to write a text in which the young characters were fascinated by the post-War cultural models of the American world. Luc, Léonce and Josette dream of becoming the new protagonists of the movies that they passionately watch. They want to mimic the deportment of Lauren Bacall or Humphrey Bogart, they want to have money (dollars by all means!), to splurge on American goods, to live another (a different) post-War American Dream that the glittering universe of Hollywood delivers to them without ado. Faced with the threat of a misapprehended Communist-socialist utopia and the lure of certain American models mediated by the illusion of the big screen, what is it that the adolescents in „Le grand vestiaire” should choose? Might there be no other way, no other models to follow? And what Gary hints at is this third way, since Luc is not quite as orphaned as Oliver Twist, in that, unlike that absolute orphan of the Victorian Age, he does have a token that is meant to keep his father’s memory alive: a copy of Pascal’s „Pensées”. The boy keeps this book in awe, stuck in his pocket, touches it and often rereads it, as if it were a precious talisman meant to remind him, when he finds himself at crossroads, what life’s true values are. Moreover, on the margins of Pascal’s book, his father had jotted down his own thoughts and musings, his own questions and his own answers to the great problems that he, in his turn, had faced. A model of sacrifice and bravery under the direst circumstances, this book and the effigy of the long since departed parent symbolize the redemption which, at the end of the way and at the end of all the adversity that he is about to face, Luc may find. Which proves that sometimes, even in the most difficult situations, literature can still save the world: if not the entire world, at least the ones who have not yet forgotten to read.

Romain Gary, „Le grand vestiaire” („The Company of Men”)/ „Marele vestiar”, translation into Romanian and notes by Adina Diniţoiu, Bucharest, Humanitas Fiction Publishing House, 2021

Translated into English by Mirela Petraşcu

Scrie un comentariu