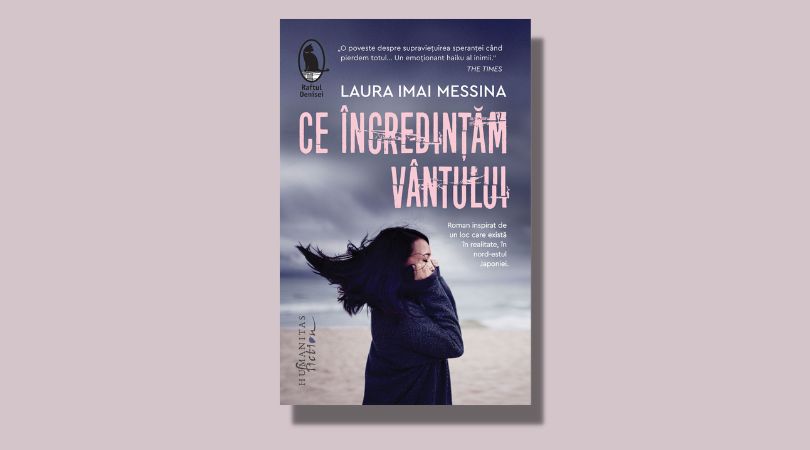

They call it the Wind Phone. It is a small booth, with an old telephone equipped with a dial and a handset, placed in the middle of a garden on Mount Kujira-yama, in the North-East of the Japanese Archipelago. After the devastating tsunami that hit the coast of Japan on 11 March 2011 and to which over 15,000 people fell victim, people of all ages looked for this phone booth and used the old, disconnected telephone to reach, in their own way, their loved ones departed from the living. It sounds like an incredible account or, at best, an inconsequential anecdote meant to surprise, even to shock, public opinion in Japan or elsewhere. And yet, it is real fact. These things happened indeed, the telephone really exists, and, alongside the touching stories of the people who have used it, it was the starting point and source of inspiration for Laura Imai Messina’s compelling novel „The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World: A Novel” („Quel che affidiamo al vento”). The exquisite Romanian version of the novel („Ce încredințăm vântului”), published by Humanitas Fiction Publishing House and signed by Smaranda Bratu Elian, offers a touching, fluent, expressive, fluid and poetic translation of each and every page of the book.

Published in 2021, having instantly become a best-seller in Italy and in all the countries where it was translated – into over twenty languages – and with the film rights already purchased, this novel, with crystal-clear pages and of an apparent simplicity that sometimes surprises and disconcerts Western readers while simultaneously winning them over, is a story about life and death, loss and reconnection, deep sadness and grief impossible to depict in words, as well as about the human being’s capacity to start all over again and to overcome difficulty. With the help of others, with the help of time that passes and heals, at least partially, even the deepest of wounds. But above all, with the help of the Wind Phone… Devoid of useless sentimentalism, with an art of narration that has sometimes been compared to David Foenkinos’s best pages, with almost impressionistic touches but also with that typically Japanese quality of saying a lot in very few words, Laura Imai Messina writes the story of Yui. And that of Takeshi. But also the story of their respective daughters – one here, the other beyond. And, last but not least, the story of those no longer here, those who perished when that surge rolled over the people in the fateful spring of 2011.

During one of her radio shows, Yui, the woman who lost her mother and her three-year old daughter to this terrible calamity, hears from one of her listeners about the existence of this unusual telephone – the Wind Phone, placed in Otsuchi, a small town devastated by the tsunami, and decides to go there herself. It is during this long, exhausting trip from Tokyo to northern Japan that she meets Takeshi, the widowed doctor whose daughter has no longer spoken since her mother’s premature death. And, with this meeting, the woman tries to set her memories – and her own life – in order. Because, right after the disaster, Yui lived in a shelter alongside other survivors, waiting to find her mother and daughter, convinced that the reunion would take place, as she knew that they had observed the authorities’ rules and had pushed on to a shelter. But days go by and the chances of finding anyone alive are ever fainter, so that Yui starts feeling that everything is falling apart around her – and in her soul. She therefore starts counting the days, but she no longer lives, she just waits, even if, rationally, she knows that a miracle is no longer possible, so the only thing she can still wish for is for the bodies of the ones she has loved most in the world to be found. Meanwhile she watches the people around her, each involved, much like herself and yet slightly differently, in small repetitive rituals of fright, expectation, hope and loss of it. People who cry or refuse to eat, people who gaze into vacancy or look obsessively at the few photos they managed to save from the disaster, a man carrying an empty painting frame everywhere and looking at the world through it, as if from behind an illusory screen meant to offer him protection from the threats around… and so days and nights go by, making Yui go on with her life, find a home and go to work – none of which actually means that she truly lives. This is the context in which she finds out about the Wind Phone, about the people who use it convinced that the old telephone can somehow carry their words and feelings to the loved ones, in the otherworld. Next to Takeshi, whom she befriends, Yui enters the phone booth, but is unable to speak. However, she will keep coming to Otsuchi once a month, despite the distance and the fatigue, in the hope that, eventually, she will be able to say something to her mother and to her little girl.

„To me, the Wind Phone is a metaphor that suggests how precious keeping close both joy and pain really is. It is not a tourist attraction. Don’t look it up on a map”, Laura Imai Messina wrote in the „Important Note” which she placed at the end of her book. And the author added: „On writing this book, I understood how important it was for me to recount hope, that the role of literature was to suggest new ways of existing in the world, to concatenate the dimension here with the dimension there. For there are places in the world that should keep existing beyond us and what we have experienced in them. Places that should last, whether we visit them some day or we never do it at all. One of these places is the Wind Phone”. Confessing that she herself had made it to Bel Gardia, in Otsuchi only years after she had heard about the unusual telephone, Laura Imai Messina said in an interview: „As soon as 2011 I read a press article about that place, and the story I have now written seemed to be heaving in sight back then, as if I had already had it in my mind. I knew that I would write it down some day, but right after that tsunami, which strongly hit me as well, I felt that I had to somehow take a step back and be able to find deep down the necessary detachment and force to approach such a painful subject”. And she added: „Do not hazard to go all the way to Kujira-yama unless you really intend to pick up the receiver of that unwieldy device and speak to the ones you have lost”.

Once uttered, words are not only apt to reach the ones beyond, but are also apt to bring solace, and ultimately healing, to the ones here. And to help them start all over again. To help them keep living, but truly living, for the sake of those who are close to them in everyday life, but also for the sake of those who will never leave them and who will continue watching over them from beyond. Obviously, healing is a long-lasting, difficult process, entailing a heightened awareness that one must never try to forget the ones who are gone, but to somehow live for them as well, afterwards.

Born in 1981 in Rome, Italy, Laura Imai Messina, who reached Japan when she was twenty-three to study Japanese language and culture (subsequently specializing in Japanese literature, as she was passionate about various aspects of Japanese feminine prose – particularly about the way in which they were reflected in Yōko Ogawa’s fiction – and authoring an excellent doctoral dissertation on maternity in Japanese and European literature) and who then settled there with her husband and children, Sosuke and Emilio, also confessed that, right after the 2011 calamity, she had been surprised by the way in which the events had been perceived beyond the borders of Japan and by the way in which the Japanese people themselves had lived through those moments. Because, while the rest of the world seemed exclusively worried about the potential consequences of the accident that had affected the nuclear plant in Fukushima, the Japanese people focussed on the aftermath of the tsunami and on the ensuing human tragedy (tragedies). It is for this reason that „The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World” centres precisely on this aspect, focussing on the suffering of the people who survived the giant killer wave and depicting characters (Yui and Takeshi) that are emblematic, not as some socially or nationally important figures, but by their very ability to express the pain of so many tormented, bereft souls. Hence the choice of the extraordinary metaphor of the Wind Phone, that unique place on Earth where the human voice and all the thoughts of someone in tormenting pain are entrusted to the wind, in a belief defying all logic and reason that they will reach, in the otherworld, the loved ones who are no longer here. Symbolically, thoughts turn into words capable of covering any distance, even the one between the living and the dead. And the Wind Phone is that place where this can actually happen, as long as words are carried by the wind to the nether world and can bring back, from the same nether world, the so-much needed hope.

But once uttered, words are not only apt to reach the ones beyond, but are also apt to bring solace, and ultimately healing, to the ones here. And to help them start all over again. To help them keep living, but truly living, for the sake of those who are close to them in everyday life, but also for the sake of those who will never leave them and who will continue watching over them from beyond. Obviously, healing is a long-lasting, difficult process, entailing a heightened awareness that one must never try to forget the ones who are gone, but to somehow live for them as well, afterwards. And the Wind Phone does make Yui and Takeshi understand this, at the same time as it brings together not only the living and the dead, but also the living and the ones living close to them. Laura Imai Messina possesses the gift of phrasing, or, when not, of suggesting all of these, in a novel so haunting in its apparent simplicity and so expressive that, more often than not, it leaves the reader in tears. Moreover, the actual story is interrupted by short chapters that resemble, at times, the delicate Japanese engravings or a telling haiku or, at others, contain rough data on the disaster, mentioned with the minuteness of a documentary, entitled as follows: „The Tohoku Catastrophe According to 10 January 2019 Updates”, „Other Sentences Fujita-San Would Utter”, „Things Bought for Her Little Girl (Never Ever Used) Found by Yui about the House”, „Two Things Found by Yui the Next Day, while She Was Googling the Word <Hug>”. Poem-like themselves, these short fragments provide the readers with yet another perspective on the narration and on the characters’ lives, reminding us once again just how important the petty things, the small joys, the details that make us smile or find within ourselves the courage and power to move on really are. Here is, for instance, how the novel ends, precisely in two extraordinary poem-like fragments: „Yui’s First Words over the Wind Phone”: „Hello? This is Yui. Mother, this is Yui.” „Yui’s Next Words over the Wind Phone”: „Hello? Sachiko? I am here, this is Mummy.”

Laura Imai Messina’s prose is more than once reminiscent of Kazuo Ishiguro’s highly elaborate style and of the atmosphere of his best writings. But with her everything works, symbolically, the other way. While in Ishiguro’s fiction the ease of the present suggests, by apparently insignificant details, that sadness will eventually come, that it is never far from people or things, „The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World” opens with the depiction of the moments of grief, loss and sorrow, despondency and abandonment, only to afterwards give, by means of places or objects that seem insignificant at first sight, the vision of hope, smiles and a new beginning. Even after a tsunami.

Laura Imai Messina, „The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World” („Ce încredințăm vântului”), translated into Romanian by Smaranda Bratu Elian, Humanitas Fiction Publishing House, Bucharest, 2021

Translated into English by Mirela Petrașcu

Scrie un comentariu