Translated into English by Mirela Petrașcu

What happens to a marriage when the husband, who has been married for only two years, is found unconscious, after a (seemingly?) double suicide attempt for love, next to a woman whose life can no longer be saved? Naturally, once the wife hears all these details, the marriage cannot but fall apart, becoming, in a split second, a glass vessel torn to pieces. But what happens if, in spite of what has happened, the spouses still have feelings for each other? This is but one of the questions that Teru Miyamoto’s novel Kinshu: Autumn Brocade tries to answer. Because this is the key situation in this book, the event that impacts on the protagonists’ lives to a much larger extent than they areprepared, at first,to accept or even to understand. It will be ten years from the terrible events and from the divorce that delicate Aki and reckless Yasuakieventually get before the two are fully capable of looking back and, at the same time, of genuinely reflecting on their own feelings.

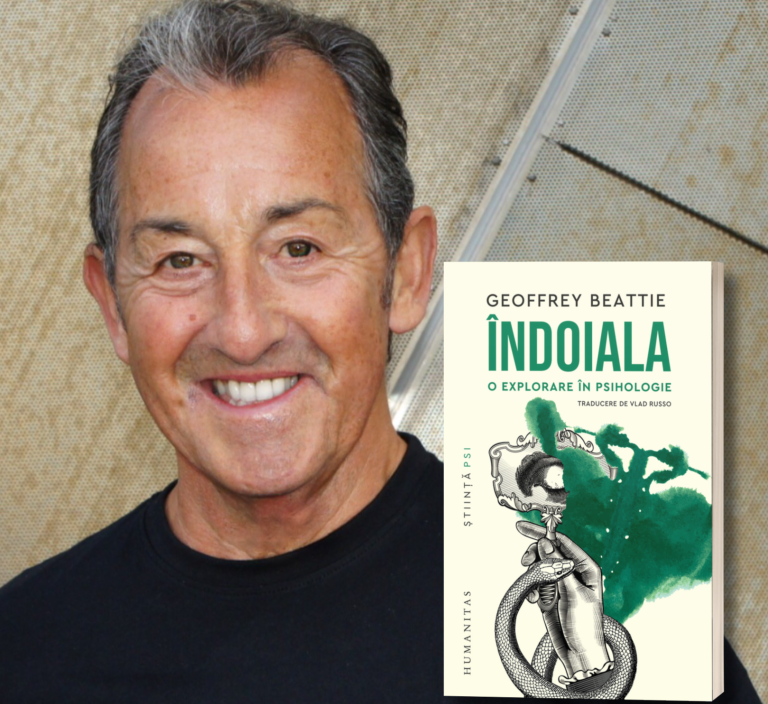

Almost unknown in the West, despite the unanimous appreciation he has long enjoyed in Japan, TeruMiyamoto gained some notoriety – at least in the circles of the Western cinephiles passionate about the world of the Far East – mainlydue to the screen versions of his books River of Fireflies and Phantom Lights and Other Stories. Published in 1982, Kinshu: Autumn Brocadeis in fact the first of his booksto have actually transgressed the borders of Japan, having been translated into several languages and having become hugely successful. But, apart from the somewhat shocking subject (yet unable for even a moment to exceed the shock caused to Western readers by writings such as Fumiko Enchi’sones – suffice it to mention, in this respect, Masks or The Waiting Years), apart from the epistolary technique (exquisitely used, however, in modern Japanese literature by Yasushi Inoue in The Hunting Gun or partially by Shusaku Endo in Silence) and apart from the constant conjoining of the protagonists’ feelings with the elements of nature (the undisputable master of which remains Yasunari Kawabatain Snow Country and The Sound of the Mountain), on having read this novel, the reader may rightfully wonder what it is that makes the text hold and what it is that makes it enchant. For Autumn Brocade is indeed a text that enchants its readers and holds them captive, from the very first page to the last, in a fictional world that the writer has woven with amazing craftsmanship.

A closer reading of the novel will show that Autumn Brocade does make a stand, even in the context of contemporary Japanese literature, precisely by the writer’s ability – the true value of which has not always been adequately perceived or highlighted – to try to give an answer (but never a single, undisputable one!) to those questions that the protagonists themselves sometimes refuse to think about. Firstly, to the previously mentioned question: what happens when, despite events such as thoseimpacting on Aki and Yasuaki’s marriage, the two still have feelings for each other? But the problem is that, out of pride or because they give in too easily to the pressure exerted by Aki’s energetic father, the two choose to separate without even trying to give their marriage a second chance. And whenthey meet again by chanceten years later, both changed, she – a wife incapable of loving her new husband and the unhappy mother of a child with a severe physical handicap and he – prematurely aged, dabbling in dubious ventures that leave him destitute, constantly changing partners, they realize, without speaking too much, except for a formal exchange of words, that they are not happy. And this meeting engenders a consistent correspondence, their exchange of letters having the power to clarify, even after such a long time, the events that caused their divorce, perhaps more importantly, to clarify their feelings about their present – and, last but not least, to help them make the long-postponed decisions about their future. And in this context, the sense of the belated confessions they make after ten years needs no longer be discussed, because to them it is not imperative, as perhaps it would have been tosome Western protagonists,to clarify if there is any point in analysing the past. On the contrary, what is important for Aki and Yasuaki is to find within themselves precisely the courage to analyse this mutual past and to tell each other, even after so many years and so much grievance, the truth.

Miyamoto’s novel is dominated by the specifically Japanese notion derived, as in the prose of his great predecessor, Yasunari Kawabata, from the aesthetics of the haiku, namely “mono no aware” (a concept which strictly translates as “the pathos of things”, but which also encompasses other meaningssuch as “the fugacity of impressions”, “deep feeling”, “the sadness of things”). The writer’s idea–one obviously intrinsic to the Japanese tradition – is that all the aspects of nature are beautiful precisely because their life is so ephemeral. Hence the permanent hint at pervasive melancholy as well as the urge to contemplate everything with sympathy and compassion. And if, for instance, Kawabata included in his writings actual ceremonies of contemplation of cherry blossoms or of the faraway outline of the snow-capped mountains, Teru Miyamoto’s present writing centres on the symbols of autumn, even the meeting between the two having as pretext a trip each of them takes to admire the colours of autumn on Mount Zao, while Aki’s first message to Yasuaki underlines precisely the details that define the interweaving of her feelings with the landscape she is contemplating: “The dahlia garden was on a mild slope. Only its indefinite shapecould be seen and a light scent could be detected. […] I was awestruck by so much beauty and radiance. But the loneliness one could perceive in the multitude of stars! And the awe that that boundless stretch bore!”

The sense of deep connection with nature does not exclude for even a second the awareness of universal ephemerality so that, at this point, it becomes clear that in this novel the recurrent hints at the images of autumn (the pale leaves, the leafless trees) correspond to the “kigo” present in every haiku, the element that enables the precise positioning both in the season and in the moral space of the Japanese soul.

It is not accidental that Aki’s correspondence with Yasuaki lasts for one year, from one autumn to another, both of them being convinced that this exchange of letters is meant to end at one time, after they have reached a reconciliation – be it a partial one – with the events that left an imprint on their lives. In fact, their correspondence embroiders, as if on a pre-existing pattern, on the theme of the past, but, having now reached another age and having accumulated a different life experience, the protagonists will, on having made their confessions, finally be able to truly glance at the future as well. Autumn thus becomes not only the sign of the end – the end of the correspondence between the former spouses, the end of the formal marriage of Aki – the one who finally decidesto leave her husband, who has had an extramarital affair for years – but also the sign of a new beginning, onewhich they have to find, eachfor oneself, and nourish with the memories they have only now entirely embraced. Because, on the other hand, it is obvious that the sense of deep connection with nature does not exclude for even a second the awareness of universal ephemerality so that, at this point, it becomes clear that in this novel the recurrent hints at the images of autumn (the pale leaves, the leafless trees) correspond to the “kigo” present in every haiku, the element that enables the precise positioning both in the season and in the moral space of the Japanese soul. It is in this sense that one should read the assertion of Aki who, after having separated from her first husband, became passionate about Mozart’s music and even found, starting from the symphonies she would listento in a café called – again, not accidentally – “Mozart”, that “living and dying mean the same thing.” Yasuaki’sreply runs in the same line as he understands, after many years and a lot of suffering,that living differently does not necessarily mean living the way he had dreamed ofand, more importantly,as in his letters to Aki he also takes courageto confess this realization – otherwise well hidden under the guise of the cynicism he flaunts everywhere and of his excessive self-confidence.And his self-confidence is once again shattered by the unexpected meeting with his ex-wife, who is apparently blooming and cheerful but who is,in fact, torn by the suffering that overwhelms her, as she is incapable of lovingher new husband and of really helping her severely ill son.

Yasuaki perceives at least part of her suffering the night he sees her contemplate the autumn sky in the mountains, without her noticing him. It is a night in which they both look at the same sky and at the same leafless trees, but, as emphasized in Teru Miyamoto’s novel, “from different places”, as if to reinforce Yasuaki’s conclusion: “How full of sadness life is!” In fact, the writer’s art also consists of his extraordinary ability to capture the sadness of existence, particularly the sadness of the two spouses’ existence, as well as the loneliness which they both try to live in – or dodge – so that their lives should retain at least a semblance of normalcy. And their sadness and loneliness paradoxically become, during the letter-writing which they both prolong for one year, the brocade which protects them from the cold of any autumn and which helps them try to start it all over again. Or, if not quite all, at least what is still possible.

Teru Miyamoto, „Brocart de toamnă” („Kinshu: Autumn Brocade”), translated into Romanian by Angela Hondru, Humanitas Fiction Publishing House, 2022

Scrie un comentariu