The Spanish Quarters are not just that quaint charming place which the tourists who arrive in the centre of Naples are eager to explore, especially to photograph, in order to capture and keep on camera the unique atmosphere of the narrow streets, of the old buildings or of the cafés bustling with life and colour (and of linen hanging from balconies…). They are at the same time a genuine, dangerous labyrinth in which people, especially those who were born there, must struggle in order to command respect or for fear they might go astray. A labyrinth in which, to fend for themselves, to assert themselves or even to survive, they must speak dialect unhesitatingly and, who knows, maybe even raise their voice or elbow their way lest they should be trampled over. It is a place where the word Camorra is never uttered, but where its threat nevertheless looms at all times. But it is also a peculiar world, one from which even swallows sometimes find it hard to fly; one where summer is heralded not necessarily by the sunrays or by the sound of the sea waves, but rather by the sharp, penetrating flavour of home-roasted eggplant!

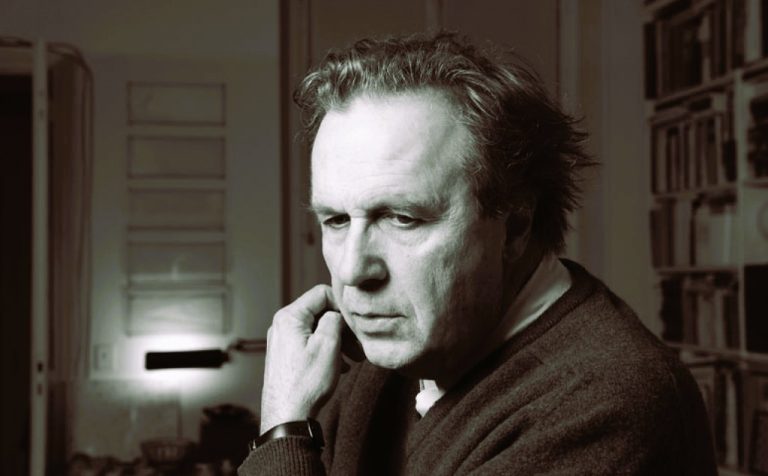

And one can learn these details not just on the spot, but also from the Italian writer Lorenzo Marone’s novel „Magari domani resto” („Maybe I’ll Stay Tomorrow”), which was published in 2017 and hit record sales in the Peninsula. This text was published after „La tentazione di essere felici” („The Temptation to Be Happy”, 2015), the novel that actually made the young writer – born in 1974 in Naples and still living there beside his family – one of the outstanding voices of contemporary fiction (let us remember that in 2017 the novel was adapted into a feature film, ‘La tenerezza’/ ‘Tenderness’, directed by Gianni Amelio). And rightfully so, „Magari domani resto” („Maybe I’ll Stay Tomorrow”) validates a remarkable literary talent and it equally wins over the readers, from the very first pages, by the fervour of the narration, by the well-balanced bouts of irony and by its ability to tell a story so humane and convincing that, at times, it seems to be part of a movie about our own lives and times. A movie still in the making.

„Magari domani resto” („Maybe I’ll Stay Tomorrow”) is a novel bustling with life, yet without ever eulogizing happiness, human kindness or generosity and without romanticizing the Southern Italian way of life or the behaviour of the locals. The characters seem seldom tempted to urge the reader, be it overtly or sub-textually, as Goethe did in his famous call, „Vedi Napoli e poi muori!” – but nonetheless the city of Naples will be so difficult to forget after reading this book, the pages of which sometimes keep the readers in tune, as if reading between the lines, with the musical notes of Pino Daniele!

Luce di Notte (Italian for ‘nightlight’) is the somewhat unlikely protagonist of this novel, much like Cesare Annunziata, the main character of „The Temptation to Be Happy”. A name that seems to have been a joke made by her eccentric, adventurous father (and a bad one at that, as her mother seems to believe, even decades later!), but one that perfectly suits the lawyer in her thirties who does not seem to have found her place in a world of appearances and of false values, in which anything (anyone…) can be bought for the right price. But Luce persists in being different, in acting differently, she obstinately defies conventions and ignores the rules of (proper?) behaviour generally accepted by a society too morally numbed to still perceive or react against the real dangers it faces. And not before long she does become, albeit unwillingly and unintentionally, a genuine light in the dark – someone brightening the lives of the people who matter and who will take to her, in spite of her hot temper and of her (bad?) habit of speaking her mind: Don Vitto, her neighbour, a former musician and voyager at sea, now willy-nilly a philosopher in a wheelchair, Alleria, the stray dog she has rescued from the garbage and adopted, Carmen, the barely literate but big-hearted mother of little Kevin, the smart, beautiful child who one fine day makes his way, though uncalled-for, into Luce’s life.

Apparently it is a mishmash of facts and names. In truth, it is an evocative motion fresco not only of the city of Naples but also of its inhabitants – some of whom choose to leave in order to set themselves free from their problems, guilt and maybe, like Luce’s father, even from themselves; others who choose to stay and struggle, well aware that this will by no means bring them complete happiness but only, perchance, some transient moments of gratification. But after all, it is these brief moments of joy that bring colour and charm into our lives. Or, as Luce puts it, “Sometimes you just happen to come home yawning, to wash your face loathing your reflection in the mirror and then, just when you are about to blame, even if for a fleeting moment, your life, something unexpected may happen, a bubble of beauty will spark nearby and light up your face and make you believe, for however short a while, until the next yawn, that all the chafing, all the grievance and injustice in the world simply cannot make you stop loving your little, at times boring, life.”

But Luce has had her own disappointments. For, even if she graduated from Law School cum laude, she could barely find a job in the law office of seventy-year old Arminio Geronimo, a lawyer who is up to all the tricks and not unfamiliar with the Camorra circles in Naples. But within one year the young woman, whose only tasks are to do secretarial work and deliver statements of defence, will have become, as she herself puts it, more informed about football and about the Naples football team rankings in various leagues than about legal matters! But she is also forced (more than once…) to repel Geronimo’s advances and to keep clear of her colleagues’ machinations – and not incidentally, in Southern Italy they are all men… Moreover, having to ride across the entire city on her old Vespa, wearing jeans, Luce is aware that every daily drive is an adventure, so she is always on the alert, always geared-up and has a mordant reply on the tip of her tongue. And she acts like this even in the presence of her mother – a practising Catholic hardly capable of expressing her feelings, much less of living by them – and of her ex-lover, a man quite unprepared to appreciate a woman of such rare honesty, whose beauty defies conventional standards.

However, one day Geronimo draws Luce in a complicated case the ins and outs of which she cannot fathom at first. Her task is to discreetly keep an eye on the mother of a child disputed by his parents, who have decided to break up. The child is Kevin and he is the one who, with his cuteness and smartness, with his incredible charm and his amazing capacity of enjoying the little things, will change Luce’s life to a greater extent than she is willing to admit. Well aware of what a difficult childhood entails and of how damaging parental misunderstandings can be for children, the quarrelsome, yet highly sensitive Luce will try not only to protect Kevin but also to make Geronimo understand that life, especially in Naples, is not a mere monochrome sketch, but an intricate painting with a profusion of nuances. So that she takes Kevin on walks, remembers what it is like to relish cotton candy and helps him settle his issues with his school-mates; and, for the first time in her life, her maternal instincts surface. And at the same time she experiences a sense of belonging to a family – a rather unusual one, made up of Kevin, the child and Vittorio, the grandfather! In fact, the depiction of their threesome strolls in the historic centre of Naples as well as the calm discussions between Don Vitto and Kevin render the liveliest pages of the novel. “‘Do you know why they are called the Spanish Quarters?’, he asked, rather for himself. ‘They appeared in 1500, when the Spanish King who had them built wanted them to accommodate the soldiers who had to suppress potential popular riots.’” But Luce also realizes how, almost imperceptibly, her own existence somehow engulfs her, no longer allowing her to pursue the Italian Dream of moving up North and making a solid career there. Is it Kevin who will not let her go or is it she herself who cannot break away from Naples and from her own memories? Or, more exactly, would a new life in Milan change in any way her thoughts and feelings, for instance? Luce understands that at first she must make peace with herself, forgive what must be forgiven and muster her courage to come to terms both with her own mistakes and with those of her parents – and be wary of repeating them.

Obviously, Lorenzo Marone’s book is fiction, having as centrepiece a fictitious protagonist, but nevertheless one who evinces more authenticity than many real people we encounter in real life. Moreover, one who, even if she gets involved (and by way of consequence engages the reader!) in events verging on the implausible, remains utterly credible and honest in everything she says and does. The author never indulges in cheap sentimentalism or melodrama, for whenever such a narrative turn is impending, irony or on the contrary, profound nostalgia reclaim the text, making the reader wonder what will happen next and eagerly await all the mysteries – be they huge or small – in the characters’ lives to be puzzled out. And it is here that Lorenzo Marone has scored an important point, in that he has devised his narrative on two distinct levels that interpenetrate from beginning to end. On the one hand there is Luce’s tumultuous present, on the other hand there is her past, which she reminisces piece by piece over the course of the events, each and every time a small impetus of today taking her back to a yesterday which she may have been too scared to thoroughly assess in order to fully understand its consequences. Along these lines, an array of other characters prominent in her life emerge (as Marone’s book is not necessarily centred on flawless plot but rather on the perpetually surprising characters!): her father who, albeit most often absent and always ready to dabble in undertakings prone to bankruptcy, has taught her how to live nicely, without fear, and to give life a smile. And above all her grandmother Giuseppina who, having spoken no Italian but only dialect her entire life, has trusted Luce and has been convinced that school and education would open her grand-daughter doors that had always been closed for her. So that, when Luce starts wondering what she should do or when she ponders on whether she should leave or, on the contrary, she should stay, she will not lack either the moral compass or the models who, without being idealized, without claiming that they always do the right thing or that they never make mistakes, will nevertheless help her choose the right path, even in a world of other paths more often beaten… Some of the characters’ replies do seem wise reflections disguised as dialogues, but Lorenzo Marone does not fall prey to pedantry even in such instances, because each and every one of these characters not only knows how to be wise or approach the ones around with irony, but also possesses the gift of self-irony.

„Magari domani resto” („Maybe I’ll Stay Tomorrow”) is a novel bustling with life, yet without ever eulogizing happiness, human kindness or generosity and without romanticizing the Southern Italian way of life or the behaviour of the locals. The characters seem seldom tempted to urge the reader, be it overtly or sub-textually, as Goethe did in his famous call, „Vedi Napoli e poi muori!” – but nonetheless the city of Naples will be so difficult to forget after reading this book, the pages of which sometimes keep the readers in tune, as if reading between the lines, with the musical notes of Pino Daniele! Moreover, alongside Luce, each and every one of us will remember just how important the apparently insignificant things sometimes are – the chirping of a bird, the grateful look in a dog’s eyes, the scent of a summer day – and how important it is that we remember to enjoy them to the full.

Lorenzo Marone, „Magari domani resto” („Maybe I’ll Stay Tomorrow”)/ „Mâine poate am să rămân”, translation into Romanian by Gabriela Lungu, Humanitas Fiction Publishing House, 2021

Translated into English by Mirela Petraşcu

Scrie un comentariu