Known in the Slovenian cultural space as one of the emblematic writers of the young generation, Goran Vojnović has once again managed to surprise and enchant his readers and the literary critics alike with his third novel, „The Fig Tree” („Figa”). For, if his first two novels, „Southern Scum Go Home!” („Čefurji raus!”, 2008) and „Yugoslavia, My Fatherland” („Jugoslavija, moja dežela”, 2012), brought to the foreground, directly or indirectly, a series of events that had affected the ex-Yugoslav world after 1990, „The Fig Tree” highlights family relations, one’s personal past, always closely connected with momentous historical events, but also the way in which people of different generations relate to that place that they eagerly seek, sometimes failing to realize that they have already found it, called home.

Published in 2016 and granted the prestigious Kresnik and Župančič Awards, considered one of the best writings in recent Slovenian fiction right upon its publication, compared to Orhan Pamuk’s or Colum McCann’s best writings, this novel is a real saga spanning several generations in the family of Jadran, the protagonist in pursuit of the great truths about the past and on a quest for self-discovery. A genuine group portrait, a symbolic image of a family shattered by the unforeseen shift of the tectonic plates in the recent history of the Balkans, a lucid meditation on the inter-ethnic relations in this region, „The Fig Tree” is equally a Bildungsroman, a tormenting book about one’s quest for identity and a text that speaks, as great literature does, about loneliness and the need to communicate, about love, its loss and recapture, about people and their abiding problems.

The narrator, Jadran Dizdar, who is in his thirties, passionate about basketball and working for a sporting bet house, seems lost in his own life and estranged from the ones who should have been closest to him. His grandfather, Aleksandar, has recently passed away under strange circumstances, under the suspicion of suicide, his father left home many years ago and his wife, Anja, has left him. Hanging in the balance and alienated as never before, Jadran is trying to find an explanation for the choices his father and grandfather made years ago, but at the same time wants to find solutions to overcome the difficulties that he himself confronts.

And, because in Goran Vojnović’s fiction the present is always influenced by the past (as in his previous novel „Yugoslavia, My Fatherland”), in his attempt to understand everything and himself Jadran must take into consideration not only his family’s history, but also the complicated history of the Balkans. It all starts in 1955, when Aleksandar Đorđević, a young inspector of forests, arrives in Buje, Croatia, close to the Slovenian border. Arriving from Ljubljana, bearing a Serbian name, he has a complicated ancestry, the significance of which will be evinced throughout the text. Captivated by the beauty of the place and attracted by this region, he decides to settle in Momjan, close to Buje, despite his pregnant wife Jana’s qualms. He will, therefore, build a house and raise their two daughters, Maja and Vesna, here. And it is also here that, alongside the family, the fig tree in the garden will grow ever bigger, turning, in time, into the real centre of the world. Not the centre of the world at large, however, or of the world marked by the ever-shifting borders of the regions of the former Yugoslavia, but the centre of the family universe which, albeit seemingly on the verge of fragmentation on more than one occasions, will eventually give meaning to Jadran’s life and will make him come to terms with his past. The fig tree is present, throughout the text, in all of the truly important moments, simultaneously highlighting the narrator’s symbolic returns in time, his attempts to recapture the past, becoming a genuine replica, over time, of the famous madeleine in Marcel Proust’s work: “I made for the fig tree under which my grandfather had put a small wooden bench from which, as he used to say, he would watch its leaves grow. Unawares, I reached for its branches and I touched a fruit. It was dark and I could not make out its colour, but, judging by how ripe and soft it was, I realized it was fig season, the season of my grandfather’s marmalade. But, before giving myself up to the sweet memories of fig picking, I saw in my mind’s eye my grandfather who, early in a morning that would no longer come, would climb up the thick, strong branches of the fig tree like a child and would pick, with his long slender hands, the ripe figs hidden under the big, coarse leaves.” Or: “Sometimes he would sit under the fig tree and gaze down there, in the valley, at the light waves of fog rolling. He was unable to enjoy either loneliness or the beauty of nature, but, unwilling to bother Jana while she was reading, he would sit still and wait for her to finish a chapter and then come over to him and recount in a few sentences the story, which she would simplify for him, as he was averse to long, complicated stories.” On the other hand, as is well known, in universal culture the fig tree is laden with meaning, being recurrent in the Biblical text – both in the Old and in the New Testament (if we were only to mention the parable of the barren fig tree, the parable of the budding fig tree and the miracle of the cursed fig tree) and in other masterpieces of universal literature, in various religions, rituals or philosophical currents.

Aleksandar and Jana’s tormented existence, their house in Istria and the fig tree in the garden – that stubborn, deep-rooted tree – symbolize the destiny of many families who, living in the former Yugoslavia, a space encompassing different ethnic groups and diverging political and religious beliefs, must nevertheless find a common way – in history and in their individual destinies. All the more so as the melting pot that this region is and has been also comes with a complicated past. We should not forget that the region where the story of Jadran’s family began was also home to an Italian community, early victims of the redrawing of frontiers in the Istria Peninsula in the aftermath of World War II. In the tumult of these historical events and amid so many changes, only the fig tree in the garden has remained unchanged, only ever bigger, unflinching before the overall madness that seems, in such short a while, to have changed everything, the world and the people alike. Years after Aleksandar’s death, the members of this family and the characters of Goran Vojnović’s novel are trying to find their points of reference again and to recover their identity. The different reactions of Aleksandar’s two daughters, the grandson’s suspicions about his beloved grandfather’s potential suicide, the cremation and funeral ceremony are the crucial elements engendering Jadran’s pursuit and, equally so, the novel. The story of his family will therefore blend with the tumultuous history of the Balkans and of former Yugoslavia and the reader will thus be faced with a complex and ambitious narrative discourse that depicts events unfolding over more than half a century and tackles many of the major themes recurrent in Vojnović’s fiction – from the pursuit of his father and of the great truths of life to the complicated relations between Slovenians, Serbs, Croats and Bosnians in the context of the emerging challenges in the aftermath of the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

This is the background against which Jadran tries to connect the dots in the past of several members of his family, to establish connections between apparently disparate events, to get a comprehensive picture of both his family and the history of his country and of Central Europe, from the period before World War II, through the Communist era to the present day. And if Jadran’s present seems to be defined by abandonment and absence (Anja leaves him, leaving her son behind as well, his grandfather is no longer among the living, his mother, Vesna, is burdened by old grievances that cannot be assuaged), the past of his family is marked by fears and uncertainty. Suffice to mention that Aleksandar, the grandfather, was born in Novi Sad in 1925 and his mother, Ester Aljehin, daughter of Moshe, a Jewish librarian, had married a dentist, Milorad Đorđević, whom she nevertheless left shortly after to move to Belgrade, where she worked as a nurse under the surname of Branislava and pretended to be a widow, in the hope that she and her son would, as far as possible, live a quiet live devoid of persecution. But, scared by the spectre of Nazism that loomed over Europe, as well as by the secrets she carried, she hastily left Belgrade in 1942 to settle in Ljubljana, which was then under Italian occupation – yet, for some reason she could not explain, she feared Italians less than she feared Germans – equally convinced that the Slovenians were less menacing than the Serbs, but nevertheless aware that she would be regarded as a stranger there as well. Years later, after arriving in Buje, Aleksandar would feel, in turn, that he had not been completely accepted by the community, which kept regarding him as an outsider.

On a narrative level, „The Fig Tree” is a real tour de force; it is a touching novel about people who seemed to have so much in common but who suddenly found themselves separated by borders or by abysses they had never ever thought about, as well as an enthralling book about the feelings and memories that can, at least every now and then, bring back together even the alienated members of a family; a text implying a lot about the narratives that make the world go round, about the importance of those stories that encompass the memory of the past and which people tell one another in an attempt at staying afloat in the maelstrom of history.

But, having written it as a family novel, the author focusses on the relations between parents and children or between spouses and thus „The Fig Tree” almost imperceptibly also becomes a subtle analysis of love and its manifold manifestations. Jadran wants to clarify his relationship with Anja while he is also trying to understand what had brought together and then set apart his parents, Vesna and Safet, by a parallel with his grandparents’ affectionate relationship, with the way in which Aleksandar would tend to his wife, Jana, who was grappling with her recollections of the past, only to then irredeemably lose her memory. The protagonist is equally affected by his father’s unexpected departure, in 1992, to his native Bosnia, as well as by the visit which, years afterwards, he paid him there, in Otoka, in the house where his father had spent his childhood. Now, looking back on it, Jadran understands that his father had tried, in turn, to regain the lost connection with his family’s past and he has, at least partially, a glimpse of the feelings that had made the latter leave his wife and son and lead an apparently eccentric life in Bosnia, one nevertheless hiding a deep alienation and mirroring, on a personal level, the general alienation that affected the entire territory of ex-Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Incidentally, Safet’s departure was triggered by a decision adopted by the Slovenian Government in 1992, whereby the citizens of the former Yugoslavia were obliged to opt for Slovenian citizenship, otherwise they would be ‘erased’ from the Civil Registry. It was a decision with tragic implications, which affected over 20,000 people in Slovenia, who lost many of their rights as of that moment. Jadran’s lucky chance was that his father had declared him Slovenian at birth… “It was only then that Safet remembered how, one September afternoon, he had entered his new-born son in a register, had turned him into letters and numbers; he remembered the pale face of the clerk on Mačkova Street, as she had explained to him that his son could be a citizen of either the Republic of Croatia or of the Republic of Serbia, because his wife had been born in Croatia and he in Serbia; he remembered what a piece of rank stupidity that had seemed back then.” In a kind of self-imposed exile, Safet will read the newspapers that are sent to him from Slovenia, to learn about his acquaintances there, to find out who has passed away, no longer knowing what ‘home’ means. On the other hand, his son cannot escape the feeling of estrangement he experienced as a teenager, when he visited his father in Otoka and did not find the idealized parent whose image he had coined in the long years of absence, but a mere man alienated form himself and from his folk, clumsy and incapable of communicating with his own son.

Jadran feels lonely and abandoned, but he gradually realizes that his father had felt the same and so had his grandfather, Aleksandar, when he had been confronted with Jana’s serious illness and had experienced, in turn, frustration, fury, guilt and tenderness, once he had sensed her inability to find her way about the world. But, after all, who would have still been able to do it in that utterly altered world, in which everything seemed to have changed overnight, especially after the outbreak of the Balkan Wars? Wasn’t Jana’s illness perhaps her shield in front of a universe disintegrating before her eyes, in front of a world losing coherence and going under in an incredible collective madness?

In „The Fig Tree”, the conflicts that affected the territory of former Yugoslavia are tackled from the vantage point of the characters’ concern with identity and nationality and are therefore assessed from the point of view of their consequences and impact on one’s personal life. Jadran lives in Slovenia, but his family tree is an intricate one, tainted by hidden rivalry between the members of the Dizdar and the Đorđević families. And even if, in the past this had not seemed to pose serious problems, things changed with the redrawing of the borders of the countries in former Yugoslavia, so that the past started to influence, even to (re)shape, up to a point, the present, in only an apparently unexpected way. Petty family feuds endorse great inter-ethnic conflicts and some of the characters’ replies mirror the disagreements between the public figures of an extremely difficult age: “It was as if someone had drawn the border through myself. They separated us by a border, they separated all of us by borders. They drew a line between me, my mother and my father”, one of the characters says at one time. And it was true because, in the former Yugoslav space, particularly in the 1990s, a wrong name could jeopardize or even destroy one’s life; even one’s memories, or at least some of them could, in turn, be dangerous – and the lives of the people in the Balkans testified to that more than once. But Vojnović’s „Fig Tree” also implies that memories themselves are the prop that every human being needs, because they are what makes each and every one of us what we are. For this reason, the author explores, from a frequently unexpected point of view, his characters’ motivations or he sometimes depicts extraordinary twists of events or choices that are apparently difficult to understand (Safet’s sudden departure to Bosnia, Aleksandar’s desire to go to Egypt, where he will even work in Cairo for a while) but which will be given, perhaps years later, at least part of a likely explanation. Alongside Jadran, the reader must patiently unravel the complicated thread of an equally complicated history to find out, at the end of the day, not only what has happened, but more importantly, why.

Moreover, Vojnović, whose familiarity with the world of cinema is evident in many parts of the present book, unhesitatingly avails himself of a series of elements characteristic of the seventh art, as well as of others which may be directly related to his own biography, in order to give more credibility to the events narrated (let us remember that he was born in Ljubljana in 1980 to a family of Bosnian and Jewish descent and he studied at the Academy of Theatre, Radio and Film there). The author lucidly examines and evokes the recent history of Slovenia and of the other ex-Yugoslav states, fully aware that it is only by taking upon oneself both contemporary realities and the political, ethnic or cultural tensions across Europe (and not only) that one can keep clear of the recurrence of the mistakes that tainted the past. And this is precisely Jadran’s desire as, in his effort to understand everything, he realizes that his family’s history has in fact replicated, over several generations, the same love stories, instances of betrayal, loyalty or estrangement, the same mistakes and the same failures. And the women – from his great-grandmother Ester and grandmother Jana to his mother, Vesna and his wife, Anja – have done their best to resist, even in the middle of a world that has so often been on the verge of dissolution or descent into chaos, while the men have been ready, more than once, to leave, to break off relations with everybody, to take themselves off, only to then try to return, but without the certainty that they would also be able to do it, always seeming to carry the past along, like an obsession they would never get over completely. Like them, Jadran also feels like a wanderer, a traveller down the paths of history and of his family’s past, but he is trying to channel his raging inner turmoil towards love and understanding instead of hatred and contempt, hoping to find the much-needed coherence that might help him heal all his inner wounds, even if Anja is sometimes tempted to believe that everything is just a plan without closure, yet another one of his illusions in a series of illusions that have defined, in recent decades, the grand history of the countries that broke away from Yugoslavia.

Goran Vojnović has distinguished himself as a highly accomplished storyteller ever since the publication of his previous novels. In „The Fig Tree”, however, his narrative art and his exquisitely mastered subtle strategies are fully-fledged, as the text of the novel is not only highly crafted and convincing, but at times truly hypnotic, the writer having resorted to a remarkable technique, compared by certain exegetes to the stream-of-consciousness one, which is further proof of Vojnović’s accomplished apprenticeship to the great masters of inter-war literary Modernism. Certainly, at times, Jadran may be perceived as a difficult narrator, as his long monologues, his flow of thoughts or the ingenious manner of expressing his feelings are not constitutive of what is generally known as ‘leisure reading’, all the more so as, here and there, they all tend to lead the reader into a genuine labyrinth of memory and/or of history.

Moreover, this narrator is trying to attain an unexpected ideal of objectivity, by somehow placing himself in the backstage of his own narration, by symbolically conjuring the voices of his family members in order to allow them to give an account of certain moments or events or even by narrating from a willingly detached, or intentionally external, perspective. Hence, probably, the varying standpoints, the sudden shifts from narrative present to narrative past or vice-versa, the apparently impromptu introduction in the text of certain characters or the much-belated clarification of particular attitudes. The narrator never ever claims full knowledge of the events narrated, everything can (and must!) be continually interpreted and re-interpreted, because only thus human existence – any human existence, not just his own – will make sense. Moreover, we cannot but notice the lyrical quality of certain pages in the book, a detail itself not devoid of significance, as Goran Vojnović also made a debut as a poet (his volume of poetry, „Lep je ta svet”, was published in 1998). Convinced that, despite his efforts, he will perhaps never fully manage either to explain or entirely comprehend some of the inner motives of his predecessors or to fathom many of the rivalries and secrets in his family – whose members are often devoid of the sense of complete belongingness to a particular space or country – Jadran realizes that what is essential for him is to (re)discover his capacity to understand and to love them all; particularly to love them, for love is the core of all things.

By Jadran’s enterprise, „The Fig Tree” not only recovers a family’s past and redraws its history but also seeks to offer an adequate understanding of the characters’ choices and deeds, of their guilt and doubts. For Jadran, retracing history and learning from its lessons are the necessary steps on his quest for self-knowledge, while for Goran Vojnović they are the most appropriate means whereby he will help his readers understand the world they live in – and themselves.

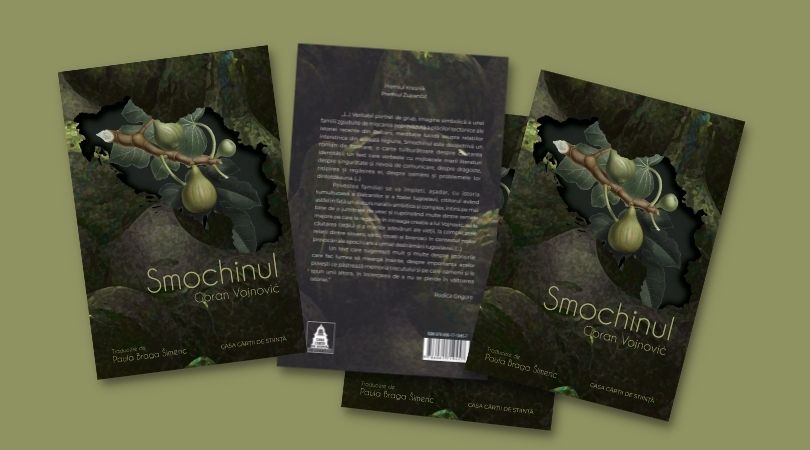

„Smochinul”, by Goran Vojnović, translation from the Slovenian and notes by Paula Braga Šimenc, Casa Cãrții de Ştiințã (Publishing House), Cluj-Napoca, 2022

Translated into English by Mirela Petrașcu

Scrie un comentariu